Boarding school is more than a place where teenagers live while they study. For many young people, it is an intense, structured environment that accelerates self-reliance, sharpens critical thinking, and teaches practical life skills. This article explains how boarding schools shape independent thinkers from early entry through graduation, balancing benefits and risks, and points to research so parents and educators can make informed choices.

Independence for teenagers means managing daily life, making choices under supervision, and learning to think through consequences. At boarding schools these skills are practiced constantly: students wake on their own, manage schedules, navigate roommate dynamics, and make academic choices with mentor support. Those day-to-day decisions, repeated over months and years, build self-regulation and habits of autonomous problem solving. Several studies show boarding students report improvements in self-discipline and maturity compared with peers in non-boarding settings.

When a child first moves into a boarding environment, the structure can feel strict. That structure is intentional. Fixed wake times, shared chores, and house systems provide predictable opportunities to practice responsibility. Over time, routine becomes the scaffolding for autonomy: a student learns to plan a study block, seek help when needed, and balance extracurriculars with rest. Research indicates boarding environments can positively influence cognitive development and organization skills, particularly in older students who can take advantage of increased academic freedom.

Boarding schools often create immersive academic cultures. Evening tutorials, prolonged access to teachers, peer study groups, and independent research projects push students to argue, defend, and revise ideas. Those practices align tightly with how critical thinking develops: exposure to divergent views, guided feedback, and repeated practice in making evidence-based decisions. Meta-analyses and surveys report a measurable positive effect on cognitive outcomes for boarding students, including gains in analytical skills and academic performance.

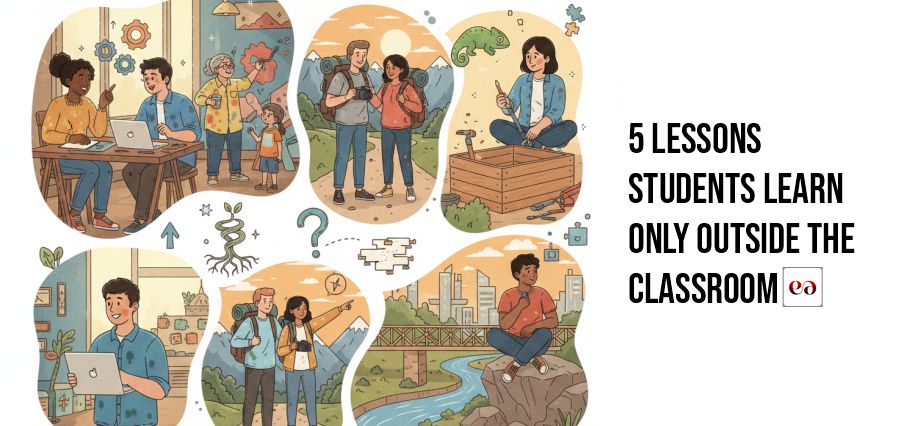

Living with peers accelerates social learning. Shared responsibilities such as running house meetings, leading clubs, or organizing service projects place students in frequent leadership roles. These settings require negotiation, perspective-taking, and ethical decision making—core ingredients of independent thought. Peer feedback loops are faster and more frequent than in day-school settings, which helps students refine arguments, correct mistakes, and take intellectual risks in a lower-stakes environment. One practical result is that many boarders report stronger leadership opportunities and collaborative skills compared with non-boarded peers.

Boarding life demands routine management: laundry, budgeting allowance, meal choices, and time management. Those tasks may seem mundane, but they cultivate practical judgment and resilience. When adolescents fail at a task, miss a deadline or mismanage a budget, they face immediate but manageable consequences. That feedback loop is essential for learning to evaluate options and predict outcomes independently. Longitudinal studies show boarders often develop pragmatic problem-solving skills that ease the transition into university and adult life.

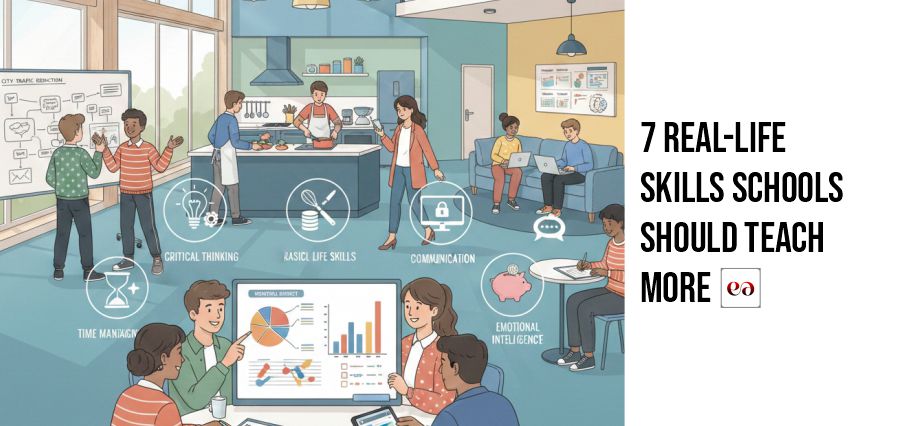

It is important to be candid about risks. Boarding schools are not uniformly positive for every child. Research literature documents mixed effects on affective and attitudinal development for some groups, and there is a well-documented conversation about “boarding school syndrome,” a cluster of long-term emotional difficulties reported by some former boarders. Factors that predict negative outcomes include very early separation from family, inadequate pastoral care, or unaddressed trauma. Good boarding programs mitigate these risks with strong counselling, family engagement, and staff training. Parents should evaluate pastoral care as carefully as academic outcomes.

Not all boarding schools are equal. The most effective environments share several features:

Parents who consider boarding should do a few concrete things. Visit dorms during activity hours; ask for details about staff qualifications and counsellor-to-student ratios; review how the school handles family contact and homesickness; and request examples of student leadership and academic feedback practices. Prepare the child with incremental independence at home—allow them to manage a budget, make travel bookings, or prepare a weekly plan, so the boarding environment feels like a continuation rather than a shock.

Boarding school can be a powerful accelerator of independent thinking when the program intentionally combines structured responsibility, rigorous academic practice, and strong emotional support. Research supports cognitive gains and improved self-discipline for many boarding students, while also warning that affective outcomes vary and depend heavily on care quality. Families who assess pastoral resources, leadership opportunities, and academic culture will be best positioned to choose a school that fosters critical thinking, self-regulation, and practical judgment.

If the goal is to raise teenagers who can reason independently, engage respectfully with differing views, and manage real-life responsibilities, a thoughtfully run boarding school often provides a concentrated environment to practice those exact skills. Do not treat boarding as a guaranteed fix. Treat it as an intensive learning ecosystem where careful selection and ongoing support determine whether a teen becomes an empowered independent thinker or merely a surviving student.

Welcome to the future of digital storytelling, where creativity meets innovation. We’re not just a magazine platform; we’re a team of passionate visionaries committed to transforming how stories are shared, celebrated, and experienced in the digital age. Join us as we inspire, inform, and redefine the world of digital magazines.

© Copyright 2025 | educationeureka | All Rights Reserved.